I am on my bed, a thin mattress on a woven mat on a packed earth floor, in a small round thatched hut with conical thatched roof, in the Kawaza village in an area outside the tiny town of Mfue in the western district of Zambia. The chickens and roosters are making a lot of noise this early morning. A few minutes ago I passed an older women, sweeping the hard-packed red earth around the separate huts that serve as the latrines, similar to our sleeping huts but with a hole in the middle of the earth and a pan of water and soap outside. These are just for the invited guests, the tourists who come this way and for whom this village has opened up these accommodations to gain some revenue, and I have no idea where the local villagers take care of their needs. There were two guards outside all night to direct us in the dark to the latrine huts. There is no electricity here. We saw no signs of electricity anywhere during the many kilometer drive from the airport except loud music from a store that obviously serves as the community center for young folks who were gathered in the dusk with blaring rock music, the same as teenagers everywhere.

I am on my bed, a thin mattress on a woven mat on a packed earth floor, in a small round thatched hut with conical thatched roof, in the Kawaza village in an area outside the tiny town of Mfue in the western district of Zambia. The chickens and roosters are making a lot of noise this early morning. A few minutes ago I passed an older women, sweeping the hard-packed red earth around the separate huts that serve as the latrines, similar to our sleeping huts but with a hole in the middle of the earth and a pan of water and soap outside. These are just for the invited guests, the tourists who come this way and for whom this village has opened up these accommodations to gain some revenue, and I have no idea where the local villagers take care of their needs. There were two guards outside all night to direct us in the dark to the latrine huts. There is no electricity here. We saw no signs of electricity anywhere during the many kilometer drive from the airport except loud music from a store that obviously serves as the community center for young folks who were gathered in the dusk with blaring rock music, the same as teenagers everywhere.

We took this ride in the back of an open safari vehicle at sunset, passing small groups of huts, 4 or 5 together, with large stacks of bound thatch leaning on one of the structures, wood fires burning for cooking with large metal pots on top of the embers, and children running and waving at us as if we were passing potentates. The landscape was dry scrubby bush and it must be difficult to eke even subsistence farming out of this soil.

Most of the children we passed, a few on bicycles which seems to be the upscale mode of transportation for those with money, were barefoot. The wind was warm on our faces and the sun went down in a brilliant red, defused by a small cloud cover. It seems little unchanged from hundreds of years ago except for the clothes people wear, some of which appears recycled from somewhere else. This is one of the most undeveloped place I have been, including both the rural villages in India 50 years ago and my overnight stops during a trek in the hills of Laos about 10 years ago.

This is the “shopping centre” which was the center point for the young people the night before. Note the red posters on the wall, the only sign we had seen of the “opposition party” political campaign in this village.

This is the “shopping centre” which was the center point for the young people the night before. Note the red posters on the wall, the only sign we had seen of the “opposition party” political campaign in this village.

Our group sat in a larger communal hut for dinner, eating Nishima, the corn porridge which is the main staple food of the country, eaten twice a day with a little side accompaniment — in our case chicken and sautéed green rape leaves. It is formed into a little ball in the fingers of the right hand and used to scoop up some of the very flavorful side dish. It was very good (I of course didn’t eat the chicken which was probably walking around a few hours before).

Sleeping that night was interesting. The guards were talking loudly outside until about 1 am. And then every time one of our group needed to find the latrines, the guards would shout, “to the left” or “to the right”, wakening me, and probably others, up. Then at 4 am there was very loud music that got louder and louder as, it appears, a truck with a blasting sound system passed by extolling the virtues of the ruling party in preparation. By 5 am the roosters starting crowing, the chickens started clucking, and the village started getting up. By 8 am, we had our sweet potato and sweet rolls breakfast.

Our tour of the village area deepened all of our impression of severe poverty. The school was one of the poorest I have ever seen — bare classrooms with well-worn wooden chalkboards and simple long board desks in the older classroom. Little decoration or educational materials in sight. Albert, the 2nd grade teacher who showed us around, said he has 85 students in his class and that there is a great shortage of teachers in Zambia. 21,000 qualified teachers were looking for jobs and there was government funding for only 5,000. The water cistern and outdoor latrines were new — and funded by U.S. Aid. But we were told the program manager comes around to check on their projects and it was required to keep the latrines locked when school was out but that every night the locks were broken and finally they gave up and left the latrines open to the locals. And now the school worries about whether their project funding is at risk.

Above, the primary school rooms and the library. The boys and girls outside latrines have been built with the US AID funded program entitled “Splash”. Below, boys playing “football” (soccer) on the school playground, happy to pose and show us around.

Near the school was the communal water bore hole, concrete with a mechanical hand pump. Many women were there, each with one or more 5 gallon plastic containers to fill with up and carry home, on their heads. The women and girls were taking turns with the effort. Some of us tried the pumping and it was quite difficult. This is an important development for this village, fresh water, any time, albeit exposed to the weather and labor intensive.

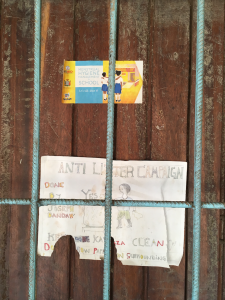

Above, a woman at the entrance to the school. And the sign on the principal’s door advertising a campaign educating girls about hygiene and a much-needed anti-littering campaign.

The women at the water bore filling their buckets. The woman in the forefront is wearing one of the cloth skirts publicizing the campaign of the incumbent president. This was the day before election day.

Our further walk took us through groups of huts, considered separate villages, with dry sparce-looking cotton and tomato fields in between Some huts were more up-scale circular brick affairs with thatched roofs. All in clusters with hard packed earth in between as the communal space for the villagers, mostly women with children. There are raised chicken coops with ladders for the chickens to ascend at night to avoid the nighttime predators. Members of our group were amazed at this but realized that the chickens who couldn’t figure this out probably didn’t make it into the gene pool.

The headwoman of Kwanza village and her granddaughter.

Passing through the fields, we end up in a small group of huts where the traditional medicine woman lives and practices. Unfortunately, she is out gathering herbs but we heard about how she was certified as a natural healer and how she looks at her patients and then goes into a trance and tells them what they need to do for their health. Actually, she sounds like a faith healer as she, like almost everyone in this area, is Christian and she quotes the bible during her trances.

Upon returning to our home village, we are seated and the women dance some traditional dances for us, bringing some of us into their circle to move our hips and stamp our feet with them as some men drum their accompaniment. They are all beautiful and seem to be enjoying themselves as well as entertaining us. And their hips movements are truly amazing, advanced belly dancing mixed with rhythmic stamping feet. Whistle blowing is included.

As we leave for our Safari camp, we feel grateful that we have been able to experience this way of life — as well as feeling fortunate that we can return to flushing toilets and running water this evening.